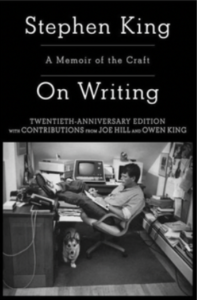

“TV really is about the last thing an aspiring writer needs,” said Stephen King.

(A warning to my readers: I talk a lot about Stephen King. He fascinates me, both as a brilliant writer and a brilliant writer about writing.)

The thing is, Stephen King is wrong, *she said humbly*. Here’s why, from an undisclosed location.

A good T.V. show is a study in tightness.

Novels allow wiggle room: Anecdotes and descriptions can slide by undetected in a crowd of 400 pages. When you only have twenty-two minutes to tell a story, there is little room for superfluous words. The writer must pack in several character arcs, a dramatic culmination, and god-willing, a satisfying ending that leaves the viewer wanting more.

An example of good TV: Frasier, the 90’s TV series built around former Cheers supporting actor Kelsey Grammer, evolved to a radio psychiatrist in Seattle. The writing is tight, even the supporting characters are fleshed out, and much is said in what is unsaid.

Example: Frasier meets Faye on a blind date.

Frasier: Of course I love Boston but well, there’s no place like home.

Frasier’s mobile rings.

Frasier: Excuse me. [into phone] Yes, hello? Uh, yes but you know

what, I’ll just have to sign those papers later, thank you.

[hangs up] Office work.

Faye: That was an escape call, wasn’t it?

Frasier: No! What are you talking about?

Faye: Come on, it’s a blind date. You wanted a way to back out.

Frasier: Oh, gosh, you are sharp, aren’t you? How did you know?

Faye’s mobile starts ringing.

A lesser writer would have had Faye answered Frasier’s question. By having Faye’s phone ring, they’re showing, not telling. There are no extra words and there’s an entire story in that ringtone.

Write your book as tight as a good T.V. show and you’re in business.

King is right in one sense: Not all T.V. is good T.V. — though bad T.V. is just as instructive. Of course, it demonstrates what not to do.

Bad T.V. disregards the Golden Rule of writing, previously noted: ‘Show, don’t tell.’ Someone will inevitably shuffle into a scene and say something taken from a book of Mad Libs:

“If we don’t get this THING to the LOCATION, the TERRIBLE THING will happen!”

Exposition removes the reader or viewer from the waterfall of dramatic events.

The playwright and former writer/director of the CBS show, The Unit, David Mamet, once wrote a hilarious memo to his writing staff on exposition and what makes good drama. (If you haven’t read it, it’s a must.)

He offers such gems as:

“ANY TIME ANY CHARACTER IS SAYING TO ANOTHER “AS YOU KNOW”, THAT IS, TELLING ANOTHER CHARACTER WHAT YOU, THE WRITER, NEED THE AUDIENCE TO KNOW, THE SCENE IS A CROCK OF S***.

“ANY TIME TWO CHARACTERS ARE TALKING ABOUT A THIRD, THE SCENE IS A CROCK OF S***,”

“THE JOB OF THE DRAMATIST IS TO MAKE THE AUDIENCE WONDER WHAT HAPPENS NEXT. *NOT* TO EXPLAIN TO THEM WHAT JUST HAPPENED, OR TO*SUGGEST* TO THEM WHAT HAPPENS NEXT.”

I guarantee that from here on out, you will not be able to hear a character say, ‘As you know,’ or, ‘We’ve got to get the DOG to the BANK before the WORLD EXPLODES!’ without an exposition flag flashing before your eyes.

Maybe you’ll feel the need to shout out, “Crock of S***!”

Sources:

King, Stephen. Stephen King on Writing a Memoir on the Craft, SIMON AND SCHUSTER, NEW YORK, 2000, p. 148.

“David Mamet Memo to Writers”